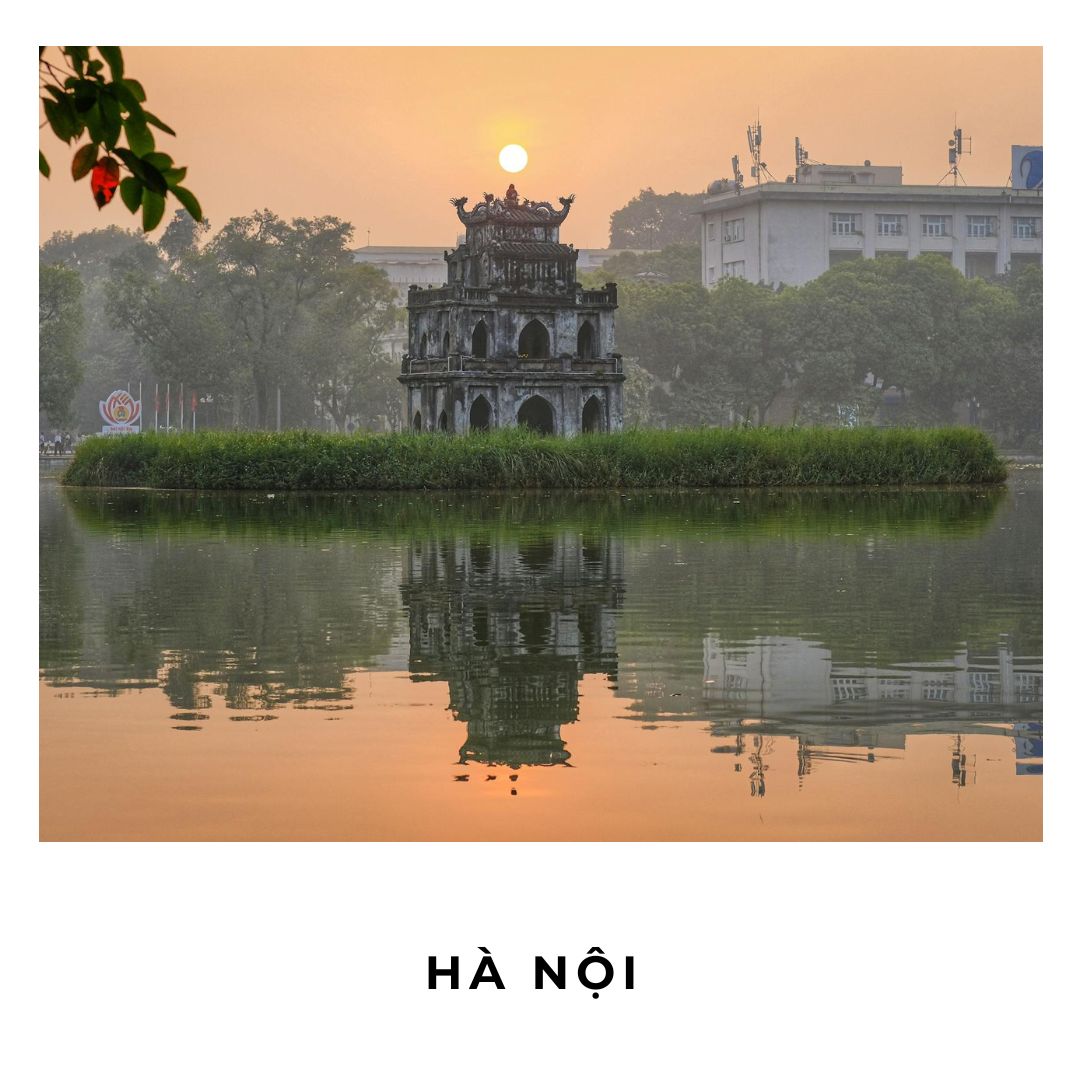

Coping with the aftermath of a war

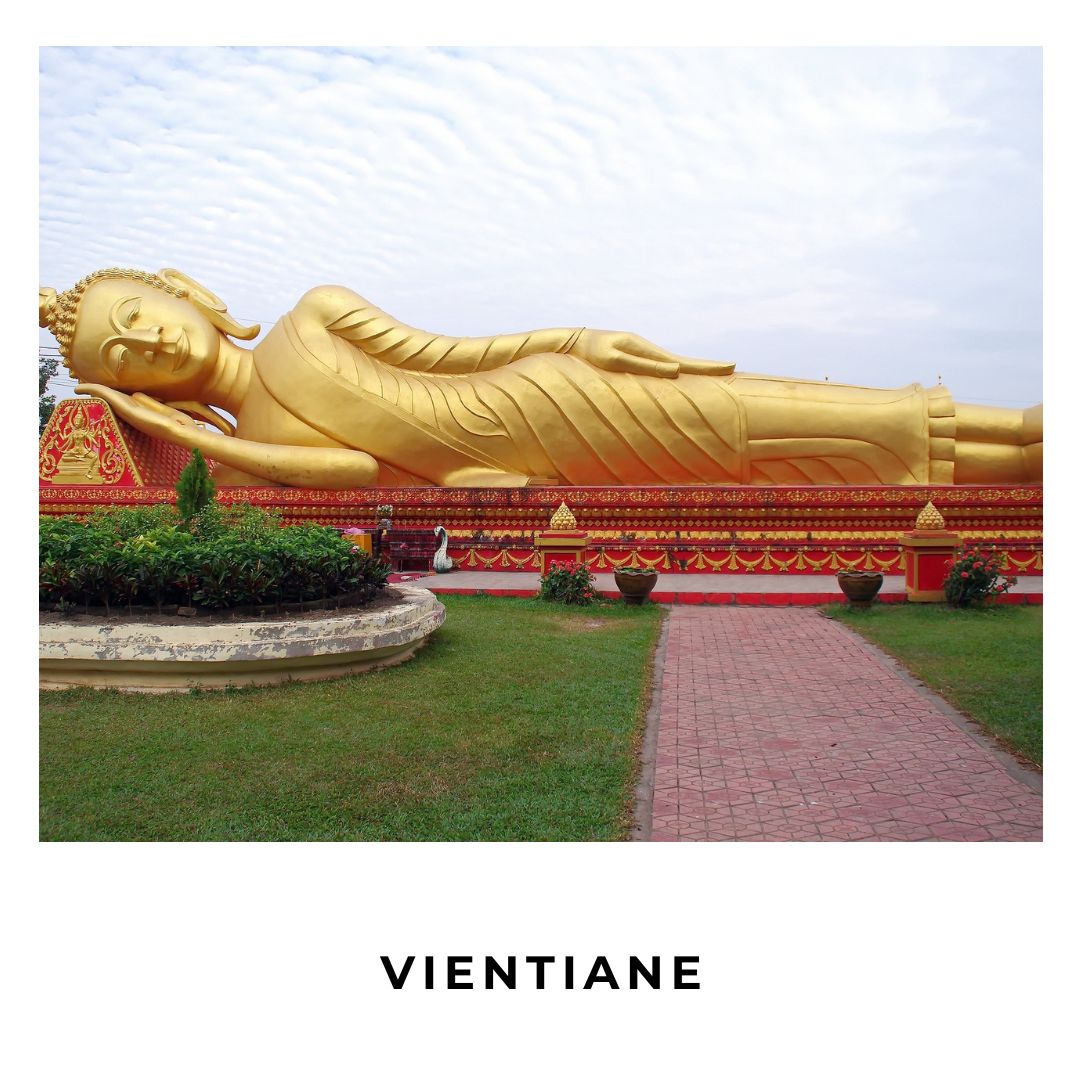

VIENTIANE | LAOS

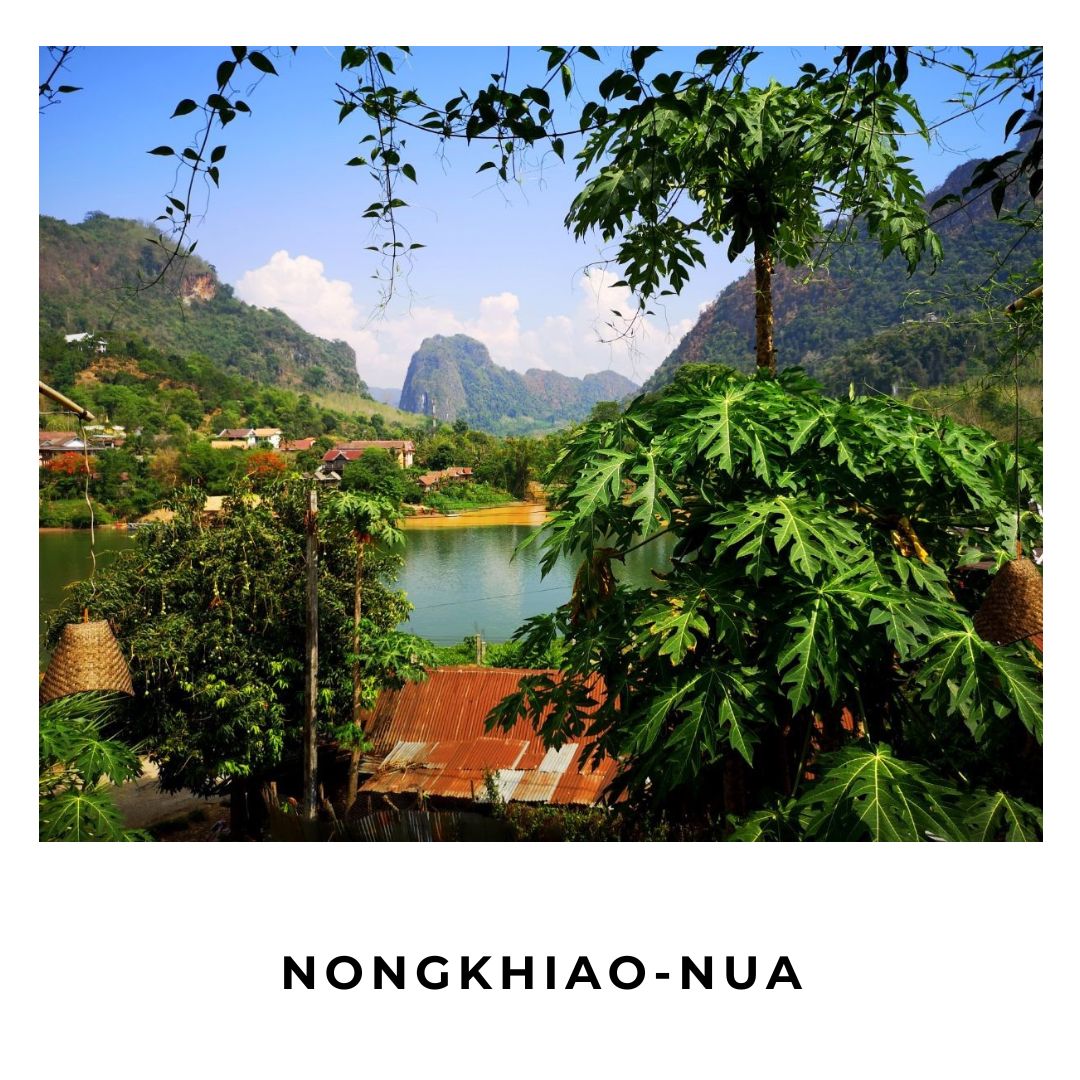

“It’s difficult to believe that the green flat fields interrupted by the colossal mountains that characterise the countryside were complete blood baths not that long ago, and the smiley, friendly locals are the descendants of a resilient generation traumatised by war”

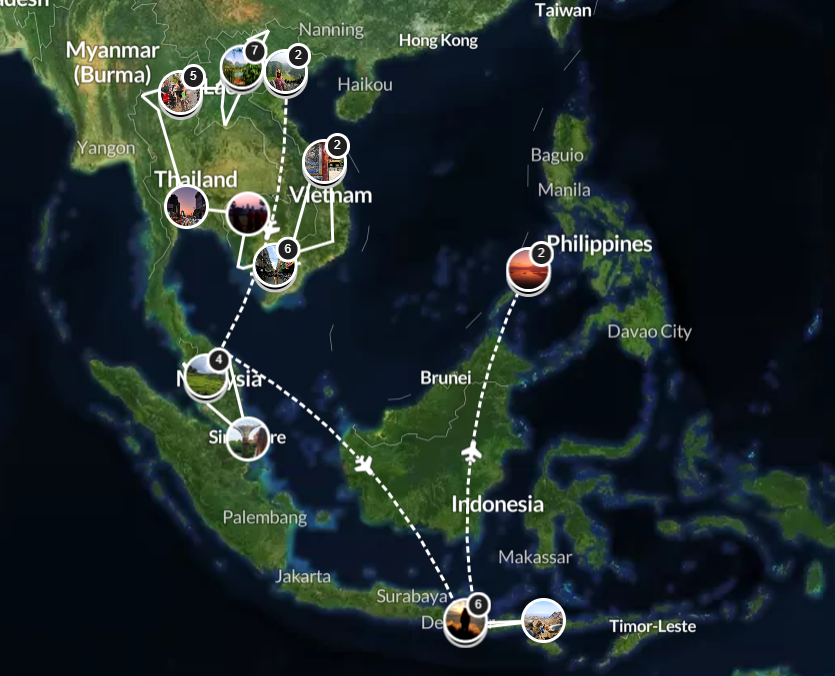

I believe that spending a considerable amount of time outside of our country, embodying the idea of being a “stranger in a strange land”, as Paulo Coelho wrote in The Alchemist, until that place starts to feel like Home, not only contributes to our self-development but allows us to gather in-depth insights about the political, economic, social and cultural realities of our vast and diverse planet, a type of empirical knowledge which truly elevates us to citizens of the world!

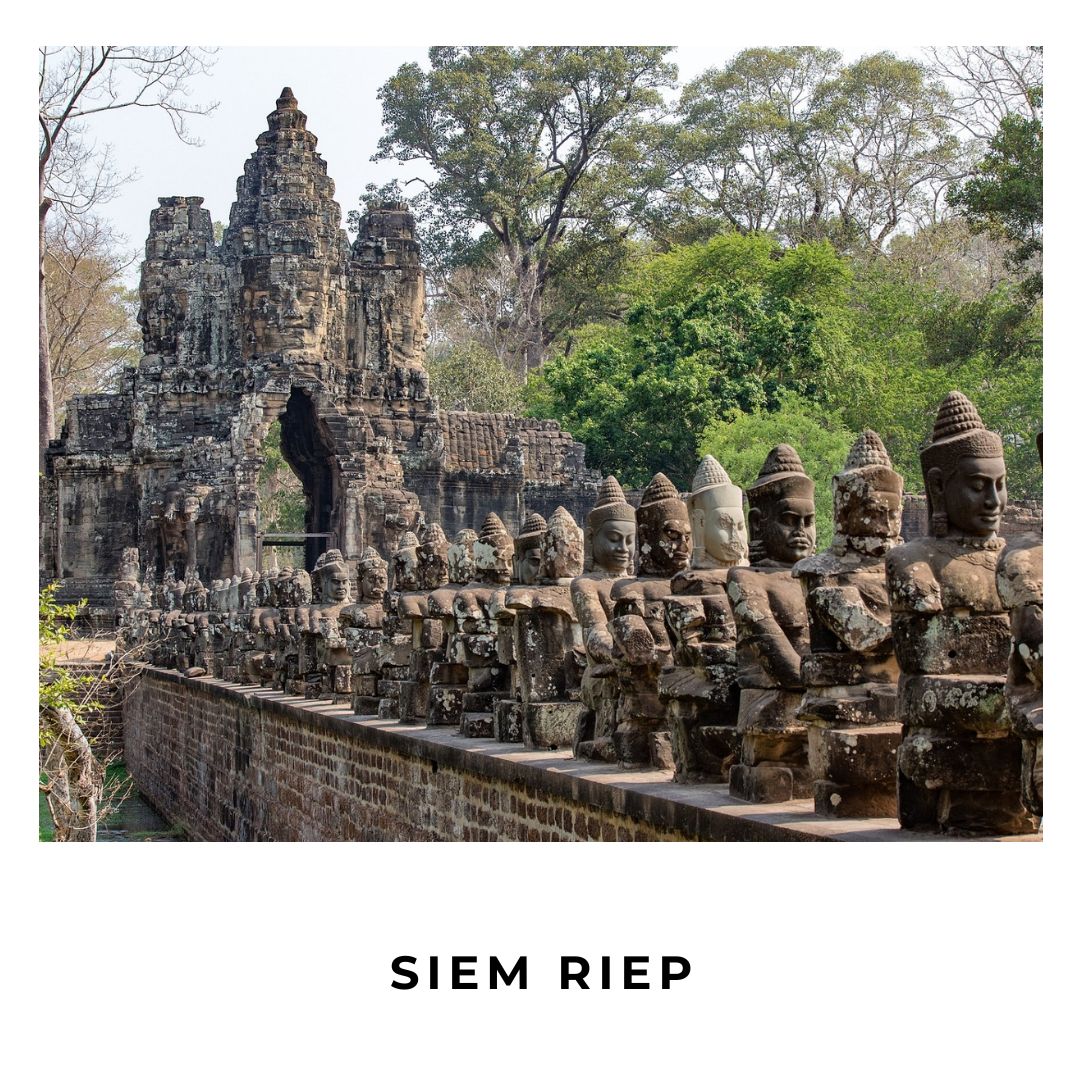

When backpacking through Southeast Asia, one aspect of the countries I became increasingly aware of was their history. In school, the only historical landmarks I remember touching upon pertained to the colonial times, so it took me travelling to Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia to learn of the recent tragic events that unfolded there.

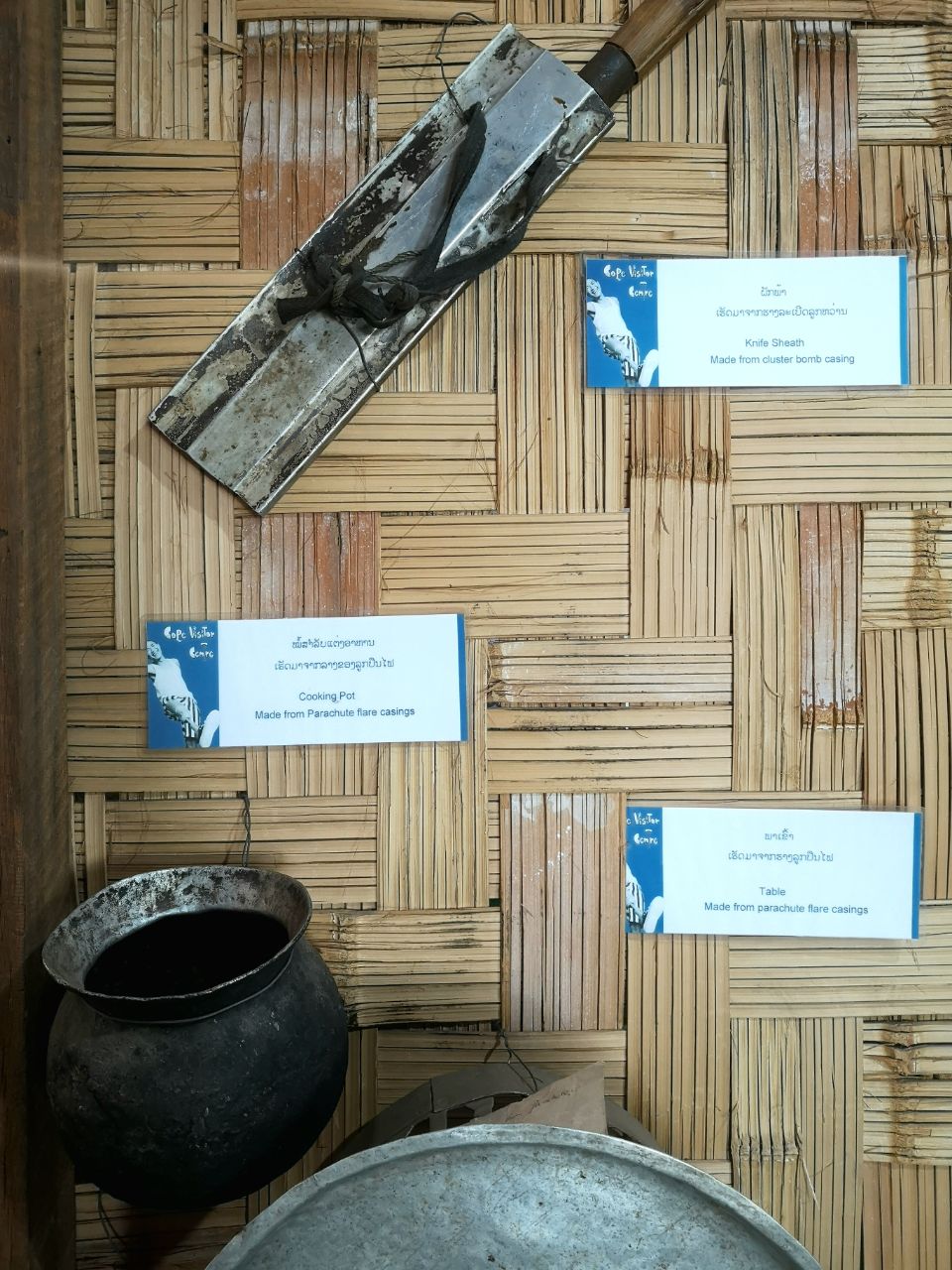

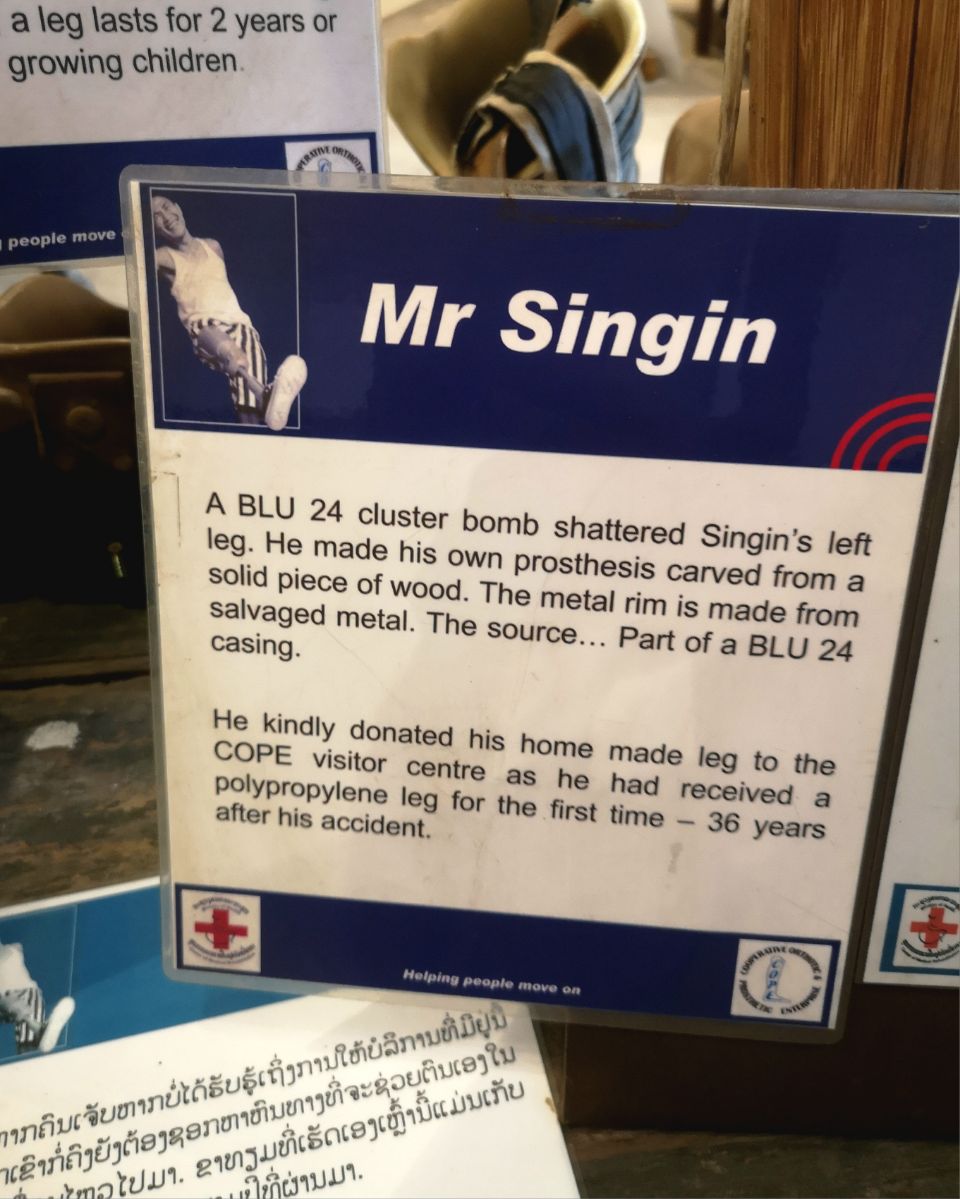

It was in the capital of Laos, Vientiane, that I learnt of the “Secret War” through the COPE Visitor Centre. From 1964 to 1973, the US dropped more than 2 million tons of ordnance on Laos – about as many bombs as there were people, which makes Laos the most heavily bombed country, per capita, in history. The clandestine nature of the war was by design: aimed at destroying communist supply lines between Laos (as well as Cambodia) and Vietnam, the bombing was conducted secretively, and details were largely unavailable due to official government denials.

COPE is both a museum, raising awareness about the impact of the Vietnam War in the region, and a rehabilitation centre, channelling funding to the manufacture of prosthetics, to help the injured by unexploded so-called “bombies” to regain some mobility and independence (that’s the name used to refer to small bombs released by cluster munitions dropped from a plane or launched from the ground). Here are some heavy facts worth outlining:

▪ more than 270 million bombies were dropped during 580 000 missions, which is equivalent to a bombing raid every 8 minutes, 24 hours a day, for 9 years.

▪ up to 30 % of these bombies failed to detonate, which means 80 million unexploded bombies remain dispersed in the territory.

▪ more than 50 000 people have been killed or injured as a result of unexploded ordnance incidents in the post-war period, among which 40 % are children.

▪ today, approximately 100 new casualties occur annually when locals are just carrying out daily activities such as farming, lighting fires, cooking or searching for scrap metal (an illegal yet lucrative trade that many communities have become reliant on).

You can learn more about this organisation here: https://copelaos.org

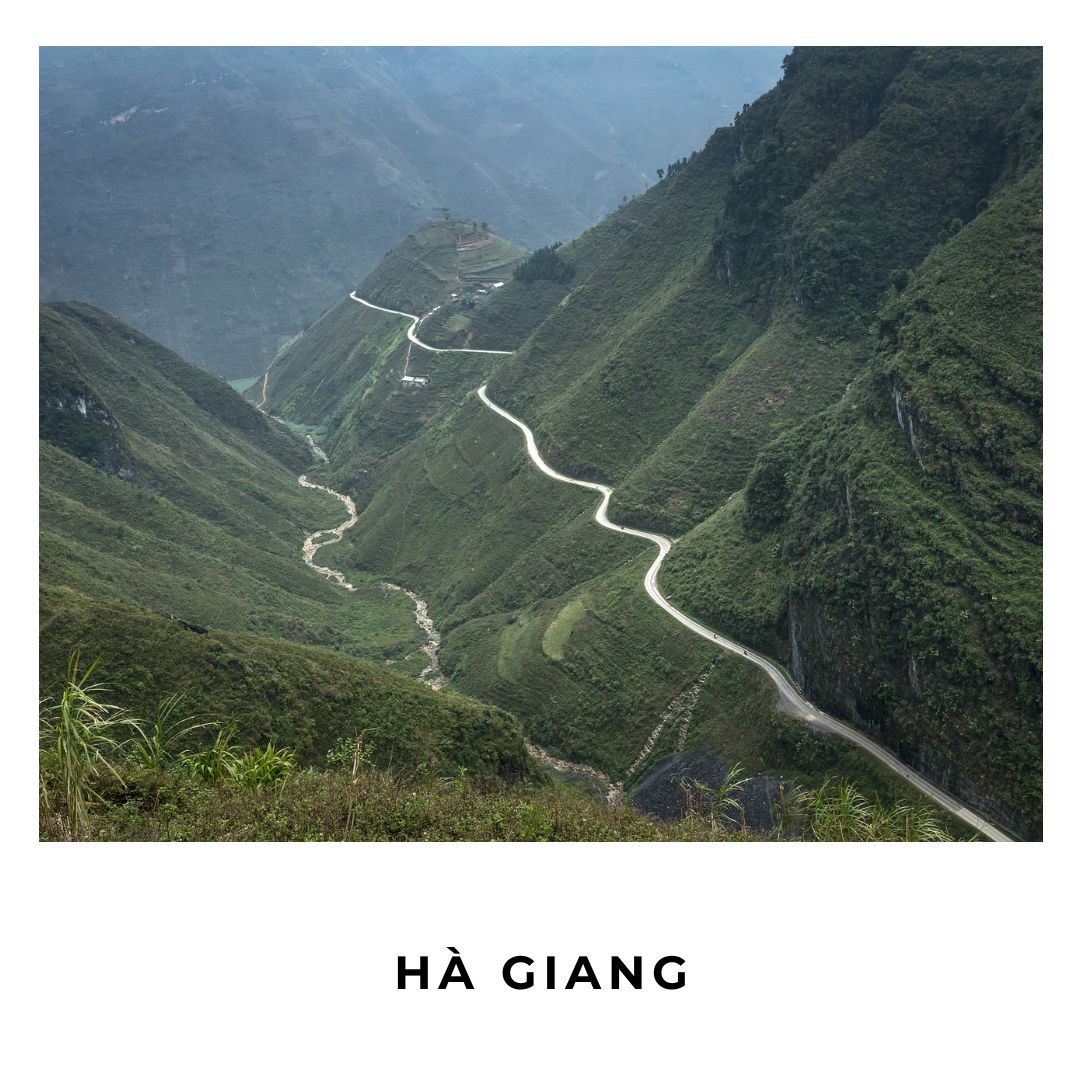

I roamed around Vientiane in bewilderment, trying to digest the ugly truths hidden behind the pristine beauty I discovered during one month in Laos. It’s difficult to believe that the green flat fields interrupted by the colossal mountains that characterise the countryside were complete blood baths not that long ago, and the smiley, friendly locals are the descendants of a resilient generation traumatised by war. And the most shocking? The UN Convention on Cluster Ammunitions which “prohibits under any circumstances the use, development, production, acquisition, stockpiling and transfer of cluster munitions” hasn’t been ratified by the one country that, indisputably, has the primary obligation to – the United States. Despite the damage inflicted by the conflict, and the undeniable developmental delay of its aftermath, cluster bombs are seen by this supreme military power as a legal form of weapon. This is the same nation that finances COPE’s projects, whilst refusing to commit to avoiding the repetition of history altogether. Talk about diplomatic and factual hypocris

photo gallery